Digital transformation calls for a leap of faith if your market doesn’t seem like it’s being disrupted.

Last year I spent a lot of time talking to learning and development people about their digital transformation (DX) journeys. They were interesting conversations, but after a while I began to notice something odd.

I should say at once that this was no organised, structured research programme. I was editor of a magazine focused on learning technologies, and I happened to be speaking to a lot of people about digital transformation because it’s a hot topic in the learning industry, where I do a lot of my work.

I talked to people from organisations large and small across a variety of sectors from financial services to charities, and there was no overarching project — just a vague assumption that I would discover some commonalities along the way that would neatly distil into a clickbaity listicle. You know the sort of thing: ‘five steps to digital transformation’.

That listicle never happened. Mostly because — and this was the big surprise — I didn’t find many commonalities.

It was slightly amazing, actually, how distinct each conversation seemed; how variously the challenge of digital was being experienced. You’d expect digital to affect organisations in different ways; however when the differences so heavily outweigh the similarities, you do begin to scratch your head. Were these people even talking about the same thing?

A tale of two sectors

The most obvious variances I found were between different business sectors.

In retail, for instance, it’s all about the omnichannel. As customers shift their behaviour to online retailing, which they’ve done in huge numbers recently, survival for bricks-and-mortar firms is seen to lay in creating a seamless customer experience across physical and digital channels, (with important work for the learning department in retraining frontline staff). The sense of a burning platform is very real in this sector. Whenever another big-name high-street brand goes up in flames — at the moment an almost weekly occurrence in the UK — it sets off the sprinklers big time in the remaining stores.

Contrast the situation in retail banking. Though driven by a similar dynamic in that its customers are migrating online at a dizzying rate (46% never visit a branch nowadays) and its premises rapidly becoming coffee shops, banks are not, by and large, having their nostrils assailed by any odour of burning.

‘Until recently, many firms feared that new entrants would disrupt key parts of their business,’ says a recent PwC report. ‘But incumbents are now figuring out their own strengths, and startups are seeing how hard it is to scale in a highly regulated industry. Both have come to see the advantages of working together.’

Which is code for ‘panic over: we put out the fire’.

There are formidable barriers, it turns out, to scaling up in financial services. A banking infrastructure isn’t something you build in your garage. Through partnerships, or acquisition, banks are absorbing their digital-native competitors, and people in financial services can afford to be more sanguine than retailers. Or so it seemed, from the group I spoke to at a dinner discussion I hosted in Canary Wharf (one of whom asked me to spell out ‘regtech’ so that he could look it up). Not complacent, but not panic-driven, either.

Singing from the same hymn-sheet?

My conversation in these two sectors, along with background reading, seemed to show that something important changes in the digital transformation message when you move your lens from a sector that is experiencing a real forest fire (retail) to one where there is a bit of smouldering perhaps, but where it looks like the boy-scouts have had all their campfires extinguished before any real damage could be done, e.g. financial services.

For a sense of what this difference might be, you can look to a sector that is in many ways the fountainhead of the DX message. The global consulting firms of the professional services sector have an agenda-setting role here, in that they make a growing portion of their revenues from advising the rest of business on how to do digital transformation. It’s the McKinseys, the PwCs and the Deloittes (backed by the intellectual heft of the business schools) who bring down the tablets from the mount; from whom we get the big-tent, widescreen view of digital transformation. If DX has some of the characteristics of a religious revival, these guys are the priesthood.

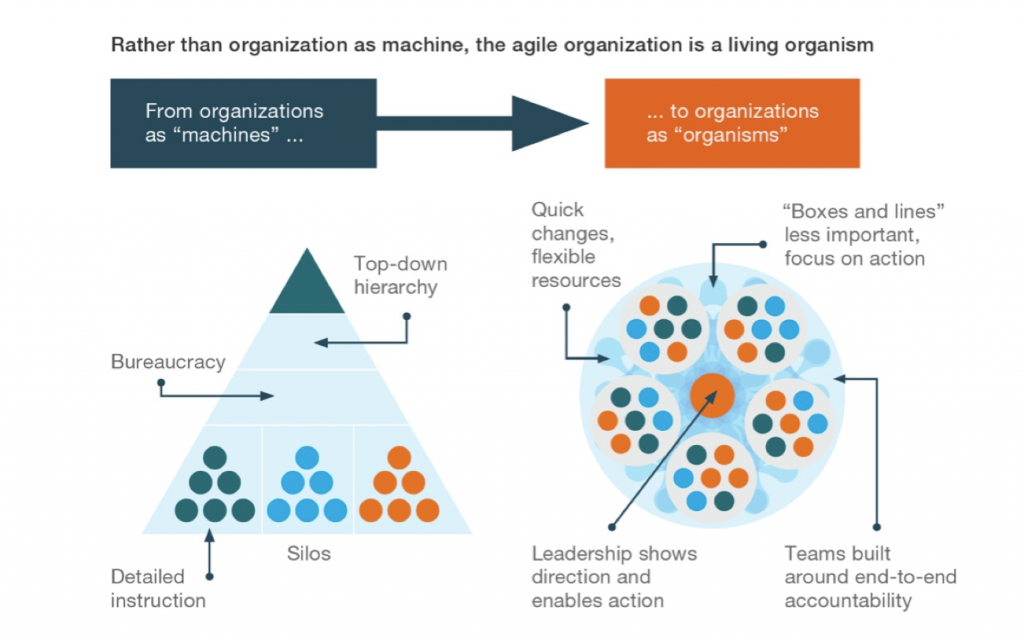

And this is the message they preach. Turn your organisation upside down: revolutionise yourself, or be revolutioned out of existence. Get agile.

Source: McKinsey

There is undoubtedly a strong theme of cultural transformation in the metanarrative of digital transformation, but my sense is that this element gets watered down once the focus moves to individual sectors.

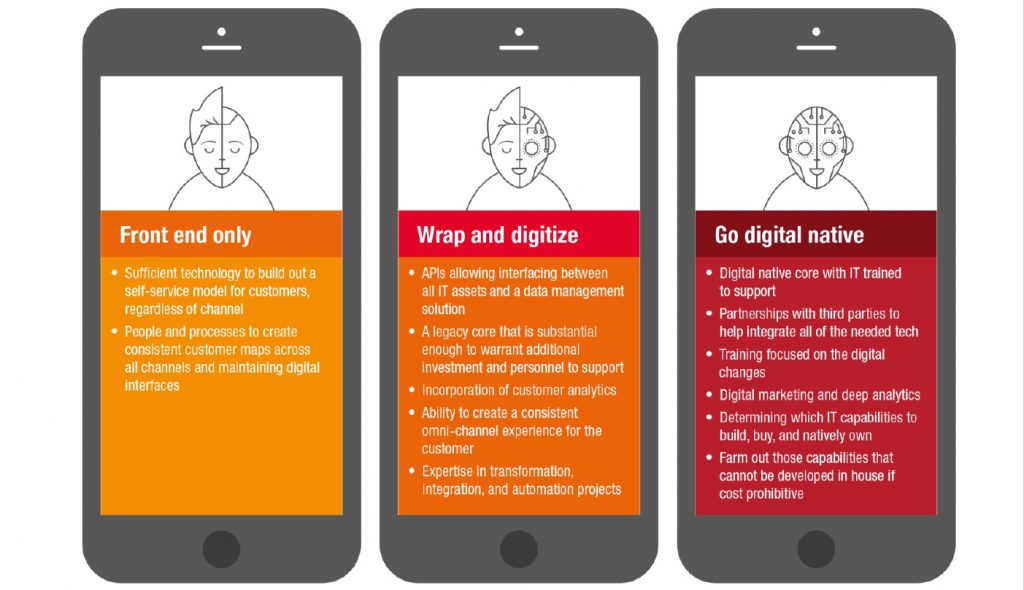

For instance, a publication from PwC’s Financial Services Institute report (‘Bank to the future: Finding the right path to digital transformation’) gives three routes to DX:

- Front-end only

- Wrap and digitize

- Go digital native

It could with justification be objected that two of these routes aren’t transformational at all.

Source: PwC

Similarly, with presentations of digital transformation in sectors such as Oil & Gas, we often see an approach that either dilutes the cultural transformation message or jettisons it all together, reducing the subject to a list of sector-specific technology trends (AI, IoT, chatbots, etc.). It’s a little as if the elephant in the room had been discretely slaughtered backstage and its body parts ready-crated for the jeweller, the pharmacist, the cabinet-maker.

What seems to be happening is that the DX message flexes according to the state of competitive forces within a given sector. If you’re on fire, transform: if you’re not, well maybe all you have to think about is managing change. The culture question doesn’t necessarily get raised.

Is it playing with words to make a distinction between transformation and change? I don’t think so. The difference is certainly not just semantic to anyone who has experienced transformation at first hand.

Pause for personal anecdote

When the company I worked for decided it was going ‘Spotify tribes’ I felt at times like a hapless bourgeois caught up in Mao’s cultural revolution of the 1960s. My budget was taken away, my marketing department dissolved, and I had to learn on my feet to lead a multi-functional team without any of the props that traditionally shore up management (compulsion, threats, bribery, coercion …) in a high-risk initiative against tight deadlines. Anyone could call out behaviour that was felt to be non-tribal and no-one’s opinion was better than everybody’s. Especially mine.

Turns out it was one of the best experiences of my working life.

Together we created a truly ground-breaking product described (off the record) by a prominent analyst as ‘the only real piece of innovation in learning technologies for the last five years’. Nothing came easily during that time, but the hardest thing was when it ended and I had to go back to a world where people still worked in the old, siloed, top-down way. I’d been through a life-changing experience. That’s transformation. Anything less challenging on a personal level is just … change.

The Parable of the Burning Platform

Why does this matter? Corporate hyperbole is a fact of life, after all. There’s a cynical view that transformation programmes happened because people got bored of hearing about change programmes. ‘Transformation’ just sounds more important. It’s sometimes necessary to up the ante a bit to get people to pay attention — which is why people often talk about ‘creating a burning platform’.

But can you really create a burning platform? Surely the platform is either burning or it isn’t. And if it isn’t, all you’re really doing is creating what fancy marketing people call a messaging platform. And this will have zero credibility with people on the ground if it isn’t attached to a real, tangible set of observable realities.

So now we’re coming to one of the core components of DX theology, the Parable of the Burning Platform.

If you read the text of Nokia CEO Stephen Elop’s memo, the place where this phrase emerges into business-speak, you quickly realise it’s not a story about manufacturing a false sense of urgency. In Nokia’s case, the urgency was real. The company had reached a pass where it had no good choices left, so Elop believed, only a dilemma: abandon the platform or face the fire. The memo detailed the company’s failures, year after year, to spot and react to what the competition was up to. And by the time Nokia’s burning platform moment arrived, it was already too late to do anything about them.

A DX enthusiast would say this is not a story about how you deal with competitive forces: Nokia had already lost that battle. It’s about innovation. The parable says you have to be proactive about innovation, put it at the heart of what you do; and that has to happen before flames are spotted on the platform, before — even — there is the faintest whiff of smoke.

This is where, for me, getting people to truly buy in to digital transformation becomes a difficult sell. Because in many cases it will involve asking them to disbelieve the evidence of their eyes and ears, which is that broadly things are going fine, and to put themselves through all sorts of contortions on the basis that somewhere out there in the depths of cyberspace, unknown and as yet unnamed, lurks a wicked fire-starter.

This sounds like Project Fear, and can lack credibility; which causes problems for those in the people function (learning, HR and comms) who have the job of selling it.

So is innovation at the heart of DX? Was that what I should be focusing on in telling this story? Not entirely.

Playing a longer game

A lot of DX narratives are about embracing new technology, however, some of the stories I heard were about the much greater difficulty in some organisations of leaving oldtechnology behind.

In the energy sector I heard from a learning technologies manager who wrote about his seven-year struggle to change learning in his organisation to a more social model, escaping the straightjacket imposed by the platforms he had to work with. The learning management system (LMS), which — for the general reader — was created to automate the administrative processes around training, still has a central role in workplace learning. But it’s primarily an admin tool, and constrains forward-thinking learning professionals who want to provide a collaborative, diverse and fulfilling set of learning experiences for employees.

This story has a much tighter operational focus than others, but what’s particularly interesting in the context of what we’re discussing here is the timeframe. Seven years. Digital Transformation didn’t really take off as a search term in Google until about 2015, and if you look back at the corporate decks from 2011 that feature the term there’s very little about culture, mindset or ‘thinking like a digital native’ in them. It feels to me like that got added later, at a point where digital native companies achieved a dominant place in the Fortune 500 and began to be taken, in some respects at least, for role models.

Meanwhile another story, from the charity sector, caused me to expand my time horizons even further. The Cystic Fibrosis Trust helps people with a cruel, life-shortening condition. Formerly, it gave a great deal of education and support through regular meet-ups and summer camps, but then it was discovered that face-to-face contact of this kind posed a high risk of cross-infection, with dangerous and potentially fatal results. The strategy had to change: the focus shifted online.

This didn’t happen last year, by the way. The new research about cross-infection came out in the late 1990s. So ever since the world wide web started to play a part in all our lives, the Trust has been on a journey with digital technology that has proved a determining factor in shaping its organisational culture. Every change towards the internet becoming more social helped the charity in expanding the support it could give. Everything is now done digitally. It probably helped that as a middle-scale charity rather than a huge corporation, the Trust’s ability to acquire big expensive tech platforms was severely limited, saving it from a lot of ‘legacy IT’ hangups.

This story inspired me, but it also caused me to think about DX and the burning platform parable in a new way.

Digital transformation needs a strong driver, as we know, and ‘creating’ a burning platform is no replacement. It simply doesn’t have credibility. But the driver isn’t always an economic imperative in the shape of competitive conditions. Sometimes it’s about the organisation having to find a different way to relate to its stakeholders.

I began to think, then, that maybe DX is primarily about relationships. And the need to recast them when they become toxic.

This could be the relationship between a buyer and a vendor, between a business and an employee (or contractor), between a content provider and a publisher, between a publisher and a vendor, between a citizen and her government. I could think of multiple examples were all these relationships have been disrupted by digital and I’m sure you can too.

I can also think of multiple examples where any of these relationships might have gone toxic over the years, and where digital technology offers the chance to repair or replace them. But we should also bear in mind that technology will in some cases have been part of what was making that relationship toxic in the first place.

All of this leads me back to design thinking and the need to focus on the end-user. In the context of learning it means putting the focus on the learner and meeting the learner’s needs (not an unfamiliar message), but it also means looking closely at the relationships between learning professionals and the vendors of learning technologies. That’s where lives the innovation in the learning industry — but also, if the truth be known, a degree of toxicity.

End matters

In the end I’ve come to the conclusion that the burning platform metaphor really isn’t very helpful with spreading understanding about digital transformation. Panic is never a good place to start thinking about anything. You might say I’ve arrived at this insight by a rather tortuous route, but in my defence I’d cite the thick black smoke given off by all those burning platforms obscuring my vision.

So sorry, no listicle, just this one thought: transformation is about relationships. What’s good in them, what’s potentially (or actually) toxic? And what can digital technology do (or stop doing) to help create more value for all concerned?